By 1993 Sega had managed to capture a commanding 65% of the console market in the US with an even greater share in Europe. This was all the result of a combination of brilliant marketing and quality games that captured the pop culture zeitgeist of the time. If you had asked most people at the time, they would have told you that Sega’s fortunes could only continue on its upward trajectory. Yet in less than a decade Sega would exit the hardware business after a series of blunders caused its hold on the console industry to slip. It is plain to see that this was due to a failure to follow up on the success of the very popular Sega Genesis and several disastrous business decisions. However, this only tells half the story. The problems that Sega suffered throughout the mid to late 90s were merely the external manifestations of the rot that was eating away at the company from within. As historian Will Duran put it “A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.”This was said in regard to the fall of the Roman Empire but applies just as much to the downfall of Sega. The history of the decline and fall of Sega’s console empire is one fraught with internal strife, foolish pride, and no small amount of idiocy.

A House Divided

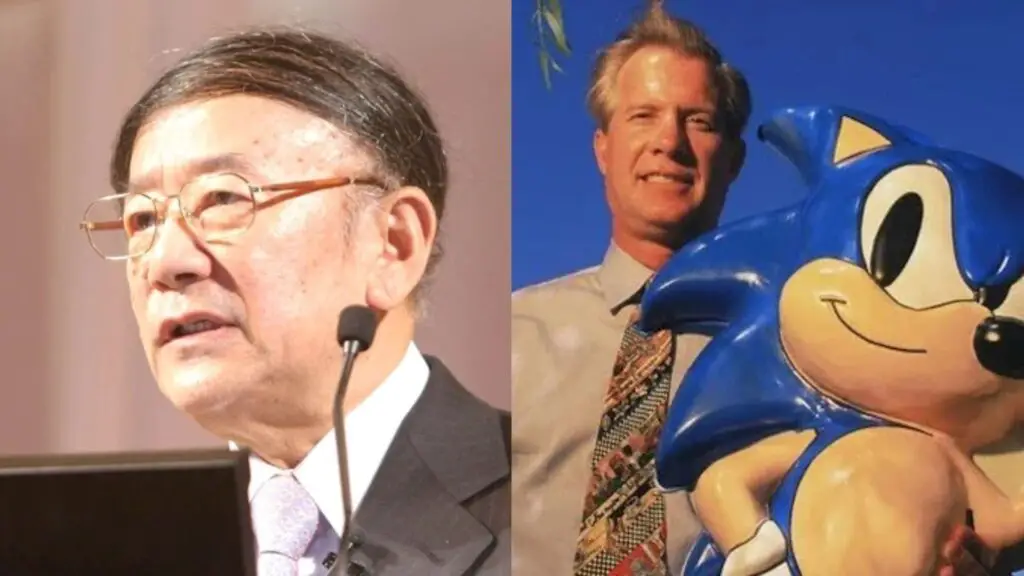

The early 90s was a time of explosive growth for Sega, starting off with a meager 6% of the market in the US compared to Nintendo’s 94%. Within only a few short years Sega had taken the lead with its 16-bit Sega Genesis managing to outsell the Super Nintendo. This success can be largely attributed to the efforts of the team at Sega of America and its charismatic President Tom Kalinske. The tireless work of these men and women turned the Sega Genesis from a bit player to a household name. In Europe, the Genesis (or Mega Drive) was also a success, largely due to the fact that Nintendo had never managed to gain a significant foothold in the region even during the heyday of the NES. However, there was one region where Sega’s 16-bit machine had never caught on and that was its home country of Japan. In Japan, the Mega Drive had taken a distant third place behind Nintendo’s Super Famicom and NEC’s PC Engine (TurboGrafix-16 in the US). The fact that the Americans had found immense success where the Japanese had failed seems to have greatly vexed the company’s executives. It has also been speculated that xenophobia may have also been a factor as such attitudes were common (and to some degree are still common) among Japanese corporations of the time. It is impossible to know with certainty if this was indeed the case, and if so how much it was present among the employees at various levels of the company and to what degree it affected the company’s decision-making. However, the possibility should nonetheless be noted and might, in part, help to explain many of the choices that were made. The Japanese had also come to resent the amount of autonomy that they had previously given Sega of America, feeling that the proverbial tail was wagging the dog. The more success that Sega of America obtained, the more resentment seemed to build up at Sega of Japan and the more that the Japanese started pushing back and attempting to reassert control. This may have begun as early as 1992 when Sega of Japan decided to unilaterally ship Sonic the Hedgehog 2 early ahead of its highly publicized global launch, something that had been the brainchild of Sega of America that it had worked very hard to try and achieve as this was the first such simultaneous launch date in the history of the medium.

Sega PlayStation

The increased friction between Sega of America and Sega of Japan began to be felt in earnest when development began on what was to be Sega’s next-generation console. Sega of Japan’s internal research and development teams had begun work on what would eventually become the Sega Saturn, though in this early stage, it was initially planned to be significantly less powerful than the final product and focus primarily on 2D games with internal debate amongst developers as to whether it should utilize CDs or cartridges. Enter Sony, fresh from its broken deal with Nintendo, and the fate of its PlayStation project was still far from certain with many higher-ups in the company being hesitant to enter the console market without an established partner who knew the business. It was during this time that Sega of America entered into a business partnership with Sony. At first, this was primarily concerned with acquiring games for release on the Sega CD through Sony’s Imagesoft publishing label, but eventually, the President of Sony Computer Entertainment Olaf Olafsson contacted Tom Kalinske with an intriguing offer; for Sega and Sony to jointly develop and release the PlayStation as partners. Needless to say, this was a golden opportunity that, had it gone through, would have forever cemented Sega’s place in the console industry while allowing both companies to collectively crush Nintendo. Kalinske recognized that potential and quickly arranged for executives from Sony and Sega to meet up and hammer out a deal. From Kalinske’s point of view what was being offered seemed too good for Sega of Japan to possibly turn down, so one can only imagine his surprise and dismay when he received a phone call telling him exactly that. The official reason that was given as to why a deal could not be reached was that Sony wanted its system to focus on 3D while Sega wanted its next-generation machine to prioritize 2D; however if one reads between the lines, several additional causes become apparent. First, the execs at Sega of Japan seemed to resent the fact that this deal was being brokered by its American branch, second was that Sega of Japan seemed to take immense pride in what its own hardware team had developed and did not want any outside interference. In fact, it was so determined to bring what it had created to market that, even had the deal gone through, the engineers at Sega of Japan planned to develop and release a stripped-down version of the Saturn hardware that utilized cartridges codenamed Project Jupiter.

Sega 64

Yet another missed opportunity would come later when Kalinske received a phone call from a representative at Silicon Graphics. Silicon Graphics had made a name for itself developing high-end computer graphics workstations that were responsible for the groundbreaking CGI in movies like Jurassic Park, Toy Story, and Terminator 2. Kalinske learned that the engineers at SGI had developed a cutting-edge chipset that could be used to create a video game console more powerful and cheaper to produce than anything else on the market, and the company was interested in partnering with Sega to make it happen. Once again Kalinske referred the representatives from the company to the executives in Japan, and once again they rejected the proposed partnership. Though no official motive was ever given, it was more than likely for the same reasons why they had rejected a partnership with Sony. Silicon Graphics would instead go on to partner with Nintendo, with its chipset forming the basis of the Nintendo 64.

The main reason why Kalinske and the people at Sega of America had been so keen to partner with another company for the development of a next-generation console was due to the fear that what the engineers over at Sega of Japan were cooking up was far too weak and focused too heavily on 2D games when it was becoming increasingly clear that 3D was the future of the industry. Nonetheless, Sega of Japan insisted on staying the course despite its American branch’s objections. It turned out that the Americans were correct as when Sony revealed the final design of the PlayStation it completely outclassed the then-in-development Saturn in virtually every respect, especially when it came to rendering 3D graphics. By the time this occurred, it was too late to drastically redesign the Saturn and so the engineers at Sega of Japan instead resorted to haphazardly adding in an additional visual processing unit along with several other chips which not only greatly increased the cost of production, it also overcomplicated the system’s architecture making it much harder to develop for.

Conclusion

From these events, we can see that Sega’s ultimate fate was far from set in stone. Had smarter decisions been made, or if the suits at Sega of Japan had been able to reach an accord with their counterparts at Sony or Silicon Graphics, then we might have had the Sega Playstation or the Sega 64. We can also see how friction between Sega of Japan and Sega of America and corporate pride was causing the company to destroy itself from within. In spite of these blunders, Sega might still have been able to course correct if it could successfully release and market the Sega Saturn. Join us in part 2 as we discuss how this too ended in disaster.

Works Cited

Harris, Blake J. Console Wars: Sega, Nintendo, and the Battle That Defined a Generation. Dey Street, William Morrow, 2015